A PLACE CALLED UTOPIA

I arrived in Australia during the last days of 1993 with a return ticket to England where I was an artist and a university senior lecturer. I'd planned to stay for a month, but remained for twenty-five years. My English paintings had reflected my passion for the extraordinary life force in nature, but my art practice and life dramatically changed in Australia. I became fascinated by the paintings of one elderly Aboriginal Anmatyerre woman artist. Emily Kngwarreye lived in the remote semi-arid red centre of the country at the Aboriginal outstation of Utopia. In a chance meeting, I met her niece, Stolen Generation artist Barbara Weir. She asked me to transcribe her life stories and those of her Auntie Emily. Thus began a five-year collaboration at Utopia between 1998 and 2005 transcribing her stories and those of twelve Aboriginal women artists in Barbara's extended family. Being with them and witnessing their extraordinary culture and the power of the natural environment caused me to question all my previous ways of seeing art, the land, and the world.

The indigenous people of Australia have the longest continuous land-based culture in the world. They are custodians for specific places they call ‘country’, a term that in English doesn’t convey the profound connection they have to ancestral land. They lived in harmony with the land until 1788 when British colonisation catastrophically disrupted their lives. Their land was taken by force, often in massacres, and they were displaced far from their homelands to harsh Christian missions that forbade them speaking their native languages. It is hard to comprehend how traumatic it is for a land-based culture to not have access to their Country, nor be able to do rituals for its regeneration. Many Aboriginal people suffer from trans-generational trauma due to their ancestors’ displacement and ill-treatment, and still suffer racism and abuse.

After European settlement, some Aboriginal men worked as stockmen on cattle stations in exchange for rations of food, clothing, and blankets, but in 1967 when legislation gave them equal pay to white workers, they were fired. Few Aboriginal people ever found suitable employment until they began painting. From 1850 to 1973, the Australian government carried out a White Australia policy which still reverberates across the land. As late as the 1970s, officials forcibly took half-caste children from Aboriginal families and put them in missions and foster homes where they were often abused. Many were never able to find their families again. Officials took Stolen Generation artist Barbara Weir when she was nine years old while she was collecting water for her Auntie Emily. They took her 1500 kilometres away to Darwin. Her family thought she died and did Sorry Business death rituals, and it took Barbara twelve years to find her family again. She and many of the women in this exhibition were instrumental in Utopia having the first successful Aboriginal Land Rights claim in 1979.

While countless tribal groups and their languages did not survive, many endured. At Utopia, the Anmatyerre and Alyawarre people continue to hand down their oral culture and ancient, experiential knowledge to new generations through ancient rituals, and Dreaming stories and song cycles that once mapped all of Australia. Each Aboriginal person has Dreamings given to them through paternal and maternal lineages. Their main Dreaming comes from their father and is for their ancestral Country, while the mother bestows a Dreaming from the place of the child’s conception.

The Aboriginal outstation of Utopia is 270 kilometres northeast of Alice Springs in the country’s arid, red centre. Jenny Green compiled an Alyawarre-English dictionary and set up a batik workshop at Utopia in 1978. The women took the small Indonesian tjanting tools, wax and silk with them when they collected bush tucker and melted wax over open fires in a communal activity which they all enjoyed. In 1988, an art dealer distributed acrylic paints and canvas at Utopia, and it was predominantly women who began painting their Dreamings and Women’s Ceremony awelye designs in that new medium. Emily Kngwarreye, an Anmatyere artist, began painting in her 80s and became Australia’s most celebrated Aboriginal artist. One of her Yam Dreaming paintings achieved the highest sum ever paid for any Australian artwork at auction, yet her homeland of Alhalkere was never returned to its Traditional Owners and has remained a cattle station.

Culture, spirituality, the land, kinship relationships, and art are not separate for Aboriginal Australians. Their exciting, hybrid works of art based on ancient Dreamings and body painting designs are now internationally celebrated. There are a few Aboriginal art cooperatives which allow artists to work together on remote outstations and receive fair prices, but the artists have long suffered exploitation by unethical art dealers. Their artworks are receptacles of their sacred culture, and it is against Aboriginal Law for an Aboriginal person to paint another person’s Dreaming. Non-indigenous artists viewing these canvases will hopefully be respectful and not appropriate the dots and lines into western artworks as a ‘style’ or technique. Aboriginal people have already had far too much taken from them…

© Text and photos Dr. Victoria King 2023

More of my writings about Utopia are on my website:

Victoria King, artist and writer

|

| Hunting and gathering at Utopia. Gloria Petyarre, Glory Ngale and Violet Petyarre with a perentie lizard. Photograph © Victoria King. |

Aboriginal Women’s Dreamings

Aboriginal Law is strictly observed at Utopia, and people are only allowed to paint their own Dreamings. Yet within that restriction, they create extraordinary variations of colours, patterns, and motifs. The seven Petyarre sisters received their Mountain Devil Lizard Dreaming from their father. Arnkerrthe is a small chameleon-like lizard, and in women’s awelye ceremonies, the women sing songs, paint their bodies with ochres, and dance for its increase. During the Dreamtime, mythic Mountain Devil Lizard women created the land of Atnangkere and its sacred sites.

Women still collect bush tucker at Utopia, and yams are an important traditional food source. Emily Kame Kngwarreye’s name Kame means yam. Her Yam Dreaming allowed her to paint the sweet potato’s flowers, seeds, leaves, underground tubers, as well as awelye body painting designs. Stolen Generation artist Barbara Weir painted her mother Minnie Pwerle’s Dreamings for a particular wild grass seed, bush melon, bush tomato, and wild orange, and awelye designs for their country of Atnwengerrp.

During traditional awelye ceremonies, the women sing ancestral Dreaming song cycles and perform traditional dances for their country. The ceremonies go on for many days and nights as ancient knowledge and rituals pass on to new generations of young girls. They collect lumps of coloured ochres from sacred sites then grind it to a fine powder on a large stone. They smear their arms, breasts and thighs with animal fat then apply the ochres in designs particular to their Dreamings. A respected elder woman ‘Boss Lady’ for each country ensures the women perform the ceremonies correctly. Emily Kngwarreye was Boss Lady for Alhalkere and Weida Kngwarreye was Boss Lady for Atnangkere. When the women paint awelye designs in acrylics on canvas, they often first prime the canvases with black to represent their skin colour.

© Copyright text Dr. Victoria King 2023.

A video link below to an exhibition of the Utopia paintings:

Aboriginal artwork from Utopia

Aboriginal Women’s Paintings from Utopia

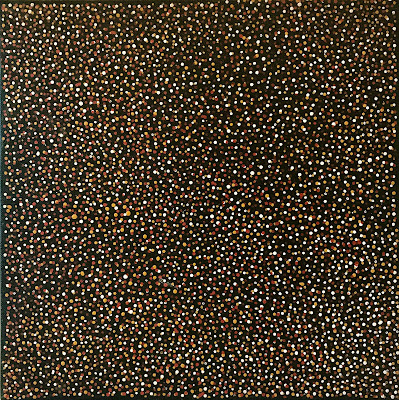

Emily Kngwarreye

Yam Flower Dreaming

1996, Utopia, 62.5 x 47 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

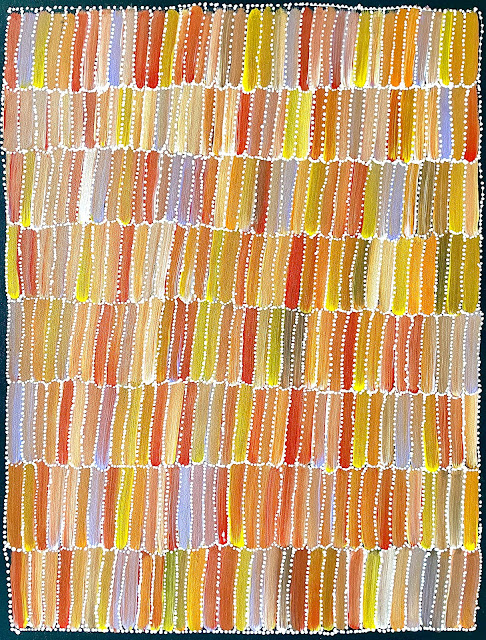

Emily Kngwarreye

Awelye Yam Dreaming

1995, Utopia, 82 x 56 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

SOLD

Minnie Pwerle

Awelye Atwengerrp, Bush Melon Dreaming

1999, Utopia, 97.5 x 60 cm , acrylic on stretched canvas

Weida Kngwarreye

Arnkerrth Awelye, Mountain Devil Lizard Dreaming

1999, Utopia, 58.5 x 58.5 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

SOLD

Jeannie Petyarre

Arnkerrth Awelye, Mountain Devil Lizard Dreaming

1999, Utopia, 55 x 55 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

Myrtle Petyarre

Arnkerrth Awelye, Mountain Devil Lizard Dreaming

1999, Utopia, 82 x 56 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

Violet Petyarre

Arnkerrth Awelye Mountain Devil Lizard Dreaming

1999, Utopia, 32 x 56 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

Nancy Petyarre

Arnkerrth Mountain Devil Lizard Dreaming

1999, Utopia, 82 x 55 cm

acrylic on stretched canvas

SOLD

Arnkerrth Mountain Devil Lizard Dreaming

1999, Utopia, 60 x 45 cm

acrylic on stretched canvas

SOLD

Awelye Mountain Devil Lizard Dreaming I

2000, Utopia, 30 x 30 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

SOLD

Ada Bird Petyarre

Awelye Mountain Devil Lizard Dreaming II

2000, Utopia, 30 x 30 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

SOLD

Barbara Weir

Awelye for My Mother's Country

1999, Utopia, 38 x 122 cm , acrylic on stretched canvas

Barbara Weir

My Mother’s Country

1999, Utopia, 120 x 38 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

Barbara Weir

Grasses

2001, Utopia, 55 x 55 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

SOLD

Janie Petyarre Morgan

Bush Orange Dreaming

1998, Utopia, 59 x 45 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

SOLD

Pauline (Polly) Ngale

Awelye Bush Plum Dreaming

1999, Utopia, 76 x 45 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

SOLD

Glady Kemarre

Awelye Bush Plum Dreaming I

1999, Utopia, 25.5 x 25.5 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

SOLD

Glady Kemarre

Awelye Bush Plum Dreaming II

1999, Utopia, 25.5 x 25.5 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

SOLD

Glory Ngale

Awelye Bush Plum Dreaming

1999, Utopia, 30 x 30 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

SOLD

Charmaine Pwerle

Awelye Women’s Ceremonies

60 x 45 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

Aboriginal Men’s Dreamings

The Australian Aboriginal dot painting movement began in 1971 at the mission station of Papunya. A kind school teacher recognised the men’s suffering from being displaced and unable to perform cultural ceremonies for their ancestral country and gave them acrylics and small boards. The men originally painted ‘secret-sacred’ designs of men’s ceremonies, but when they realized that uninitiated boys and women would see them, they covered the designs with dots. Other Aboriginal communities did not take up the practice until acrylics were introduced at Utopia in 1988, and it has always been primarily women who paint there.

Utopia artists Tommy Jones and Johnny Jones were Alyawarre-speaking brothers whose country was Irrweltye at Utopia. The marks and patterns on their paintings are specific to their Dreamings and refer to those made on the ground with leaves and flowers during ceremonies when men paint their bodies with ochre designs and perform ritual dances. The half-circle motif is a symbol for a person sitting in the sand, while the concentric circles refer to significant sites and Dreaming paths associated with Irrweltye.

© Copyright text and photographs Dr. Victoria King 2023.

Aboriginal Men’s Paintings from Utopia

Johnny Jones

Men’s Ceremony I

1999, Utopia, 60 x 45 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

Johnny Jones

Men’s Ceremony II

1999, Utopia, 60 x 45 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

Johnny Jones

Men’s Ceremony III

1999, Utopia, 60 x 45 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

Tommy Jones

Men’s Ceremony

1999, Utopia, 91 x 61 cm, acrylic on stretched canvas

Artworks on Paper

from other Australian Aboriginal communities

Judy Watson

Big Wet

1997, signed etching, 28/30

Image: 52 x 17 cm

Frame: 68 x 33 cm

Estelle (Elle) Munkanome

Jilamara

1999, Tiwi Islands

ochre pigments on signed handmade paper

Image: 31 x 23 cm

Frame: 30 x 40 cm

SOLD

Sue Pascoe

Kapi Water Dreaming

1997, Lockhart River

signed screen print artist’s proof, dark indigo blue

Image: 30 x 30 cm

Frame: 53 x 53 cm

Rosella Namtok

My Relations

1999, Lockhart River signed screenprint 34/125

Image: 29.5 x 21 cm

Frame: 40 x 30

© Text and photographs Dr. Victoria King 2023

%20Munkanome.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment